Tracking down rare Shakespearean books

On 20th June, Gregory Doran (Artistic Director Emeritus at the Royal Shakespeare Company) and Emma Smith (Professor of Shakespeare Studies at Oxford University) visited Cape Town to view a First Folio held by the National Library of South Africa - the only Folio copy kept on the African continent. TCC Director Chris Thurman was part of a small group of Shakespeare scholars, theatre makers and book history enthusiasts who joined Doran and Smith for the viewing. The next day Thurman departed on a bookish pilgrimage of his own, a three-week trip to libraries and archives in France and Germany, in order to consult some equally rare publications: translations of Shakespeare’s plays into African languages like Kiswahili and Krio.

The South African National Library (Cape Town campus)

Greg Doran holds the mic as Buhle Ngaba holds the floor

A table read of a different kind

Doran recently retired after a decade as RSC Artistic Director (and 35 years with the company), having just directed his 50th RSC production: Cymbeline, which happens to be the last play included in the First Folio. Doran is no stranger to South African shores - he first travelled to the country in 1995 when he and his late husband, the celebrated Shakespearean actor Antony Sher, staged a production of Titus Andronicus at the Market Theatre - but this visit was made as part of a longer, staggered voyage. To mark the 400-year anniversary of the First Folio’s publication, Doran is on a “Folio tour” of sorts, visiting institutions around the world where copies are housed. Smith, author of This is Shakespeare (2019) and presenter of the popular podcast Approaching Shakespeare, is a leading Folio scholar; her book, Shakespeare’s First Folio: Four Centuries of an Iconic Book (2016) was published in a new edition this year.

Doran and Smith’s visit to South Africa, which was hosted by the British Council, included numerous events ranging from a roundtable on Shakespeare in education facilitated by the Shakespeare Schools Festival to a discussion with theatre makers presented by the Maynardville Open-Air Festival. The highlight, however, was an intimate gathering to admire the National Library’s First Folio.

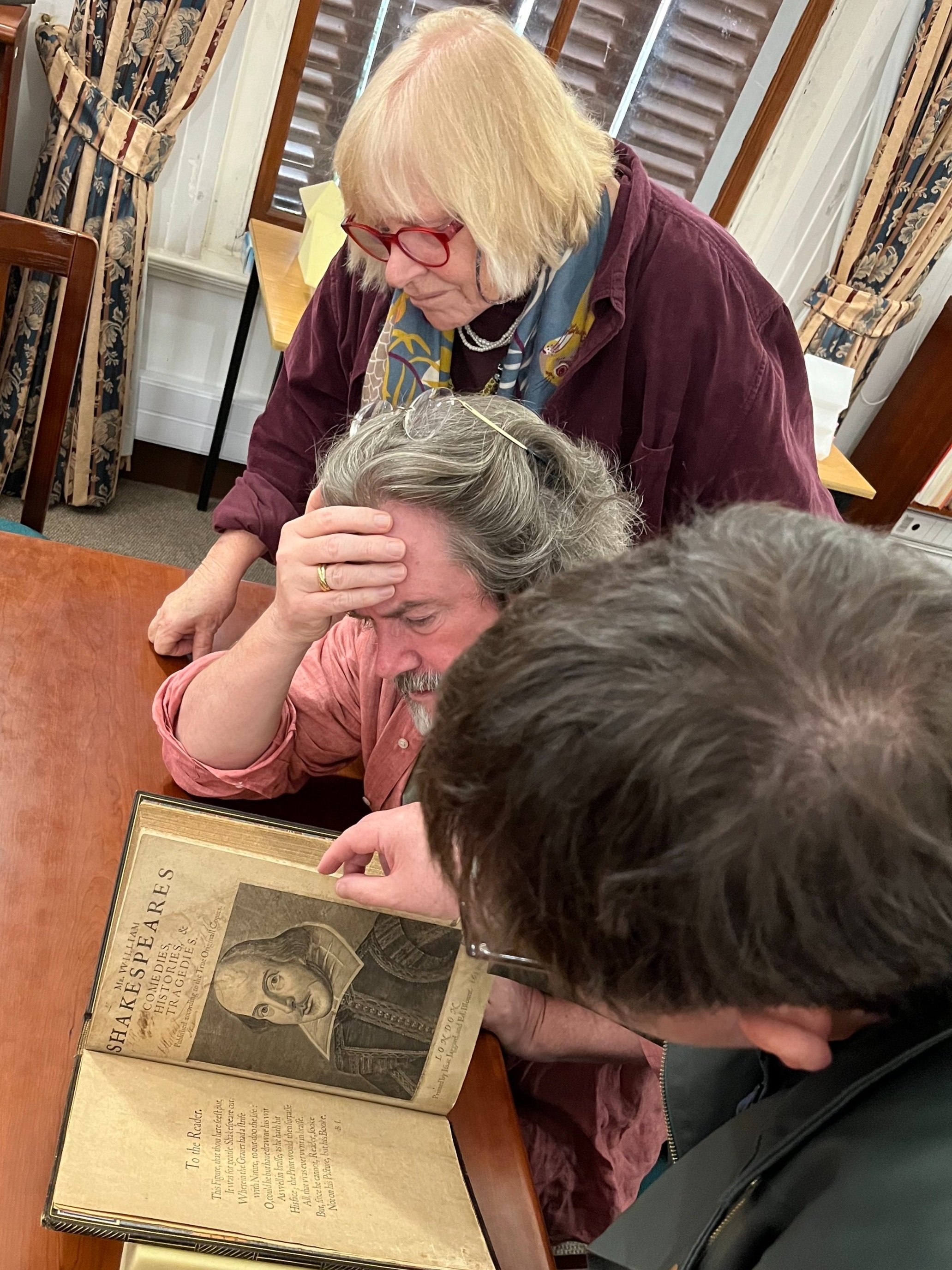

Greg Doran and Emma Smith puzzle over a mark on a blank page at the back of the Cape Town First Folio . . .

. . . and Janice Honeyman adds another pair of expert eyes!

Greg Doran with a painting of Macbeth’s witches in the Iziko South African National Gallery (part of Breaking Down the Walls, an exhibition curated by Andrew Lamprecht)

The viewing was arranged by Andrew Lamprecht of the Iziko South African National Gallery. In attendance were George Barrett and Vicky Lekone of the British Council, theatre makers Janice Honeyman and Buhle Ngaba, film makers Liza Key and Victor van Aswegen, academics Chris Thurman and Caminey Kuropatwa, and various National Library staff members. The event prompted lively discussion both about the book itself - with Doran and Smith offering fascinating observations comparing it to other Folio copies they have studied - and about the story behind its presence in South Africa.

Like the First Folio held in Auckland, the Cape Town copy was donated by Sir George Grey, a British colonial administrator who was Governor of New Zealand before and after his term as Governor of the Cape Colony (1854-1861). Grey’s legacy is inevitably a vexed and contradictory one, and as Folio scholars like Smith and Chris Laoutaris (Shakespeare’s Book, 2023) have pointed out, this ambiguity attaches itself to the Folio copies in Auckland and Cape Town: a reminder to Shakespeare enthusiasts that “Shakespeare’s Book”, and indeed the entire Shakespearean oeuvre, cannot be extricated from histories of colonial conquest and exploitation.

It is hardly suprising, then, that translations of Shakespeare’s plays into African languages have also played complicated - often paradoxical - roles in colonial and postcolonial contexts, by turns subverting and reinforcing British (English) imperialism and “soft power” across the continent. Although there is evidence of performances of Shakespeare in various African languages in the nineteenth century, the earliest known published translations appeared in the 1930s: Sol Plaatje’s Setswana translations of A Comedy of Errors and Julius Caesar in South Africa, and E.T. Johnson’s Yoruba translation of Julius Caesar in Nigeria.

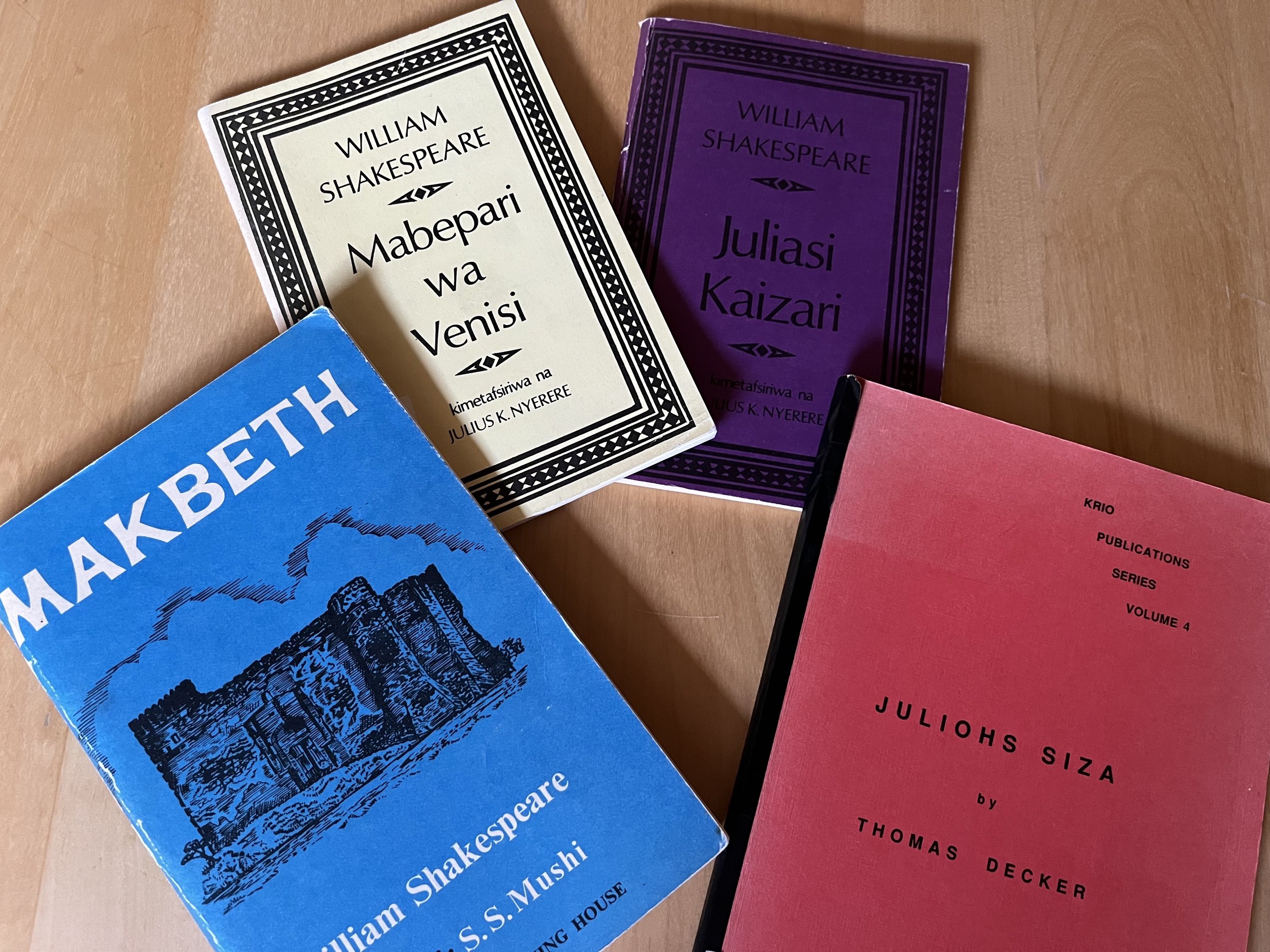

Translations into Kiswahili in the 1960s (most famously by Tanzanian president Julius Nyerere but also by his contemporary, Samuel Mushi) were seen as contributions to the post-independence practice of Ujamaa. In apartheid South Africa, translators engaged with Shakespeare to preserve and promote cultural and linguistic heritage but their work could also be seen as, in some ways, complicit in the separatist ideology of the white nationalist state. French and Arabic translations of Shakespeare’s plays by African writers and theatre makers confirm these languages’ African “lingua franca” status. Shakespeare has also been translated into numerous pidgin- and creole-based African languages: Sierra Leone Krio (Thomas Decker), Mauritian Creole (Dev Virahsawmy) and, more recently, Naija or Nigerian Pidgin (Bernard Ogini).

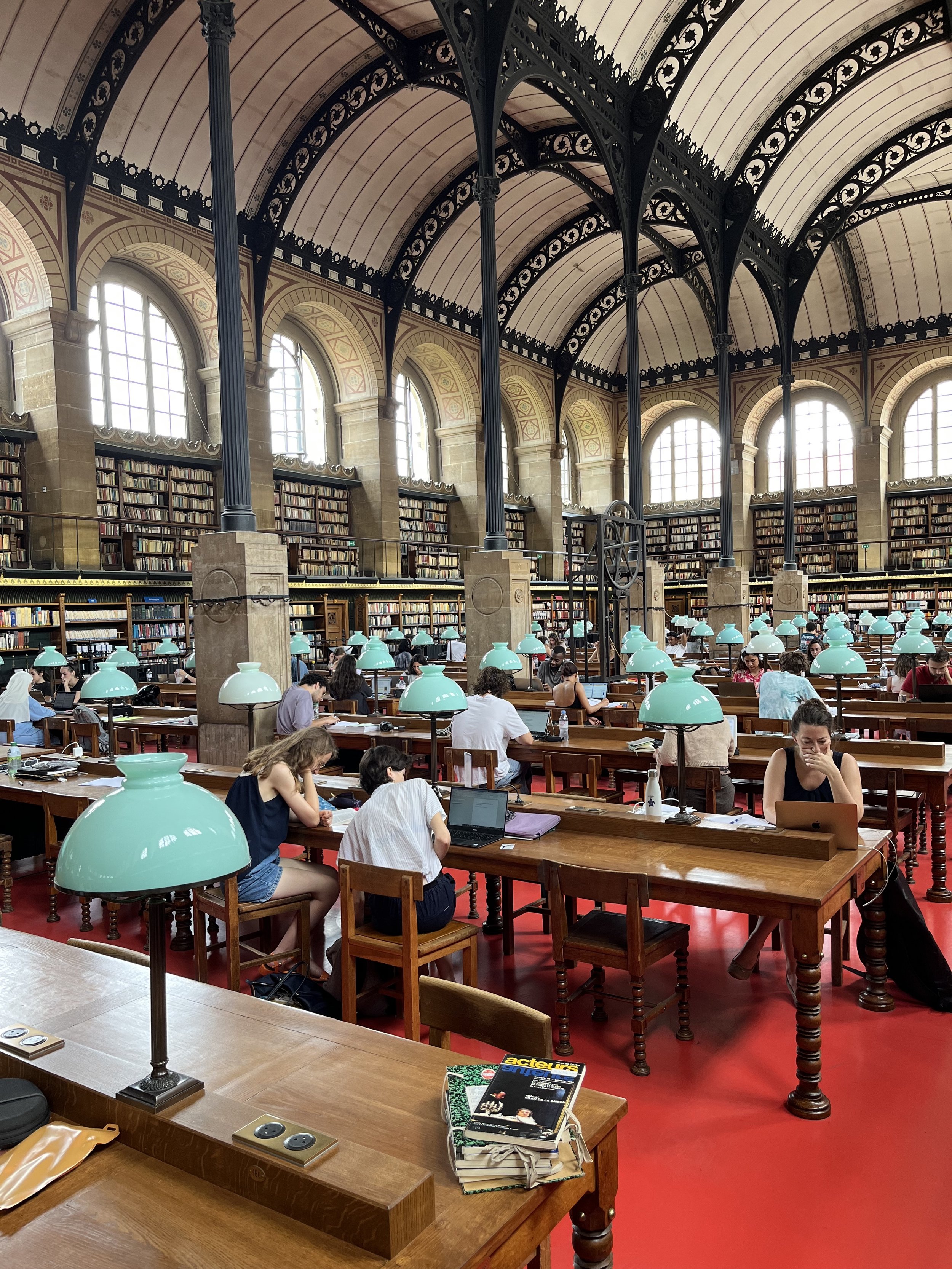

Through the Sol Plaatje Archive of Shakespeare in African Languages, the TCC aims to digitise, collect and curate as many of these translations as possible, and to give them new life by making them available to a wide readership. Currently, most of the texts are only to be found in libraries and archives, with a handful of copies dispersed around the world (primarily in Europe and the United States). The chief purpose of Thurman’s visit, then, was to identify copies of some of the key translations held in libraries in Paris and Bayreuth, to assess their condition and to begin the process that will secure them in the digital repository of the Plaatje Archive.

This trip was supported by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation’s Research Group Linkage Programme, which has granted generous funding to support a collaboration between the University of Bayreuth, the University of Cologne and Wits University under the rubric of “African Shakespeares: Translating the texts, transforming the field”.

Thurman was hosted by Dr Ifeoluwa Aboluwade in Bayreuth, where he met with scholars in the University’s “Africa Multiple” Cluster of Excellence (including a visit to Iwalewahaus), and by Prof Peter W. Marx at the University of Cologne, where he gave a lecture on some of the TCC’s recent endeavours to produce South African Shakespeares on film.

Left to right: the reading room of the Sorbonne Interuniversity Library and the imposing precinct of the French National Library in Paris; the front and back of the Iwalewahaus building in Bayreuth; some of the many translations of Shakespeare’s plays into African languages that will soon be available via the Sol Plaatje Archive of Shakespeare in African Languages.